You drop out of warp, not far from the K8 space station. You see right away what the problem is - the station's been taken over by Klingons. They're everywhere - at least a dozen battle cruisers. Almost as if they're expecting you, they immediately begin to close in.

Captain Smirk: Sensor sweep.

They're powering up weapons. There's no way your Scout ship's going to be able to take them all on. They're hailing you.

Captain Smirk: Raise shields. Power up phaser banks.

You realize that if you open fire you'll be nothing but dust. The Klingons are demanding that you to stand down.

Captain Smirk: We won't surrender. If we're going down we'll take as many of them with us as we can. Ready photon torpedoes.

Oh boy! This isn't how this was supposed to go. The scenario, as planned, called for the crew of the USS Perry to surrender. They get taken captive and find out what the Klingons are up to. Then they find a tricky way to escape and defeat them. How many times have we seen Kirk do this? This actually happened to me when I was running Star Trek many years ago. (Still own and dig the FASA rules)

This is a common GM dilemma. You place the characters in a situation where they're sure to be destroyed. The goal is to get them to either surrender or run away. I faced a similar problem in a Call of Cthulhu game recently. The characters arrived at a lost city. Their guide was immediately killed by overwhelming forces. I wanted the characters to run away. The rest of the scenario is about how they get home without their guide. The problem is that the Players want their characters to be heroes that fight to the bitter end. Makes for a short game if this is the beginning of the adventure. I blame this mindset on combat oriented games with easy resurrection.

After my Cthulhu game, one of the players asked me how I knew the characters would run away. I had a 3-tiered plan. In order of preference:

1. Hope that the Players are smart enough to have their characters run away. My description should let them know that they are not going to survive any other way.

2. One of the characters is a Naval Officer. I could tell him that in his military experience, the best solution here is to run away. This allows the Player to deal with the problem in character. He tells the other characters to split.

3. I just flat out tell them that their characters are going to die if they try to fight it out. I'll try to drop it casually, something like, "It's clear that If you stay and fight the oncoming horde, you're all gonna die. You might want to run back to the boat and cast off."

Run away and live to fight another day. I'm sure I'm paraphrasing here, but even Troupe Monty Python figured this out.

Tuesday, April 24, 2007

Tuesday, April 17, 2007

What are you doing here?

I come to in Engineering. That's the Good. I was sure we were gonna to burn once we hit atmo.

The Bad - My drive unit, nicknamed The Love Machine, ain't givin' me no love.

After a quick looky, I find some vermin's yanked parts out of The Love Machine while I was out. Welcome to the Ugly. And now the Angry. Fee, Fi, Fo, who stole my friggin' parts!?

So began my first experience with the SERENITY RPG. I love this type of game. A small crew, just tryin' to get by. My first TRAVELLER games, 30 years ago, started with a small ship and crew working to make ends meet. Inspired by Han Solo and Chewie, I wanted that personal experience. In running STAR TREK, I've always run small ship and crew games. So what do you need?

A Captain, preferably played by the groups usual leader. A Pilot. An Engineer. A Doctor. A Security Officer. That's the core group. Don't leave atmo without them. In this particular game we had the first three and two other characters. They had interesting backgrounds, but I couldn't figure out what they were doing on the ship. I couldn't even tell what postion they held in crew.

The GM ran the game well, and I had a good time, but later, when telling friends about the game, these mystery characters kept coming up. This was a Convention Game and I've run a ton of Con Games. I always make sure that the pregenerated characters I hand out have three things going for them.

1. They have a reason for being in the adventure.

2. They have skills that help out in the adventure.

3. The combination of 1&2 give the characters reasons for going through the adventure together.

I didn't get why the GM put these two characters in the game. A friend of my helped me understand. I think like a screenwriter. I only create characters that are needed for the story. If I have 7 characters for an adventure, I make sure that they ALL have a place in the story. That way none of the characters look at each other and ask "What are you doing here?"

The Bad - My drive unit, nicknamed The Love Machine, ain't givin' me no love.

After a quick looky, I find some vermin's yanked parts out of The Love Machine while I was out. Welcome to the Ugly. And now the Angry. Fee, Fi, Fo, who stole my friggin' parts!?

So began my first experience with the SERENITY RPG. I love this type of game. A small crew, just tryin' to get by. My first TRAVELLER games, 30 years ago, started with a small ship and crew working to make ends meet. Inspired by Han Solo and Chewie, I wanted that personal experience. In running STAR TREK, I've always run small ship and crew games. So what do you need?

A Captain, preferably played by the groups usual leader. A Pilot. An Engineer. A Doctor. A Security Officer. That's the core group. Don't leave atmo without them. In this particular game we had the first three and two other characters. They had interesting backgrounds, but I couldn't figure out what they were doing on the ship. I couldn't even tell what postion they held in crew.

The GM ran the game well, and I had a good time, but later, when telling friends about the game, these mystery characters kept coming up. This was a Convention Game and I've run a ton of Con Games. I always make sure that the pregenerated characters I hand out have three things going for them.

1. They have a reason for being in the adventure.

2. They have skills that help out in the adventure.

3. The combination of 1&2 give the characters reasons for going through the adventure together.

I didn't get why the GM put these two characters in the game. A friend of my helped me understand. I think like a screenwriter. I only create characters that are needed for the story. If I have 7 characters for an adventure, I make sure that they ALL have a place in the story. That way none of the characters look at each other and ask "What are you doing here?"

Sunday, April 15, 2007

What do you do?

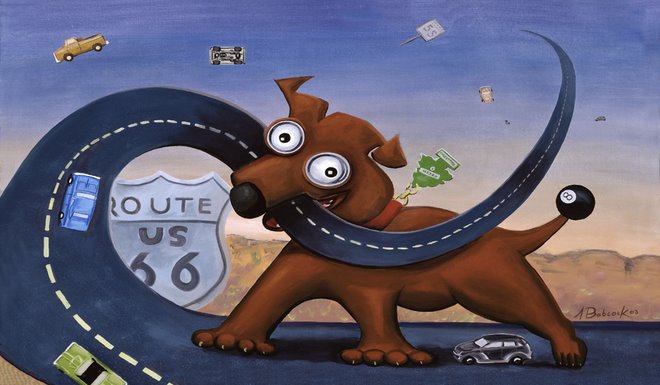

You look out across the desert and you see a large reddish-brown dog.

How large?

Easily 50 feet tall. It has goggley eyes with a hint of sickly yellow in the center. On the end of its tail is an enormous 8-ball, swinging around like a wrecking ball. It has a bright red collar. Instead of a tag, a giant pine air freshener, the size of a toolshed, swings from its neck.

What's it doing?

It trots down Route 666. Cars swerve out of its way. It growls at them, bends down and bites the road. It peels the pavement up off of the ground, like a strip of black licorice, and shakes it. Cars fly through the air and crash in dusty heaps of twisted metal. With chunks of asphalt dropping from between its teeth, it turns and looks at you. It seems to be smiling.

Smiling?

Sort of a mischievous grin. What do you do?

During the course of a game I ask the Players this question again and again: What do you do? It's their cue. They're on. It's their turn to be a hero, or die trying. That's what it's all about - what THEY do - the Players and their characters.

What they do needs to be left entirely up to them. It shouldn't be scripted. I've played in tons of games where the characters are being led through the story and nothing that they do seems to alter the story. I intentionally create situations for my Players that I don't have a solution to. I don't know how they're going to get out of the problem they've gotten into. This is usually when they come up with the most interesting solutions. If I spoon-feed them a solution, then they get through the adventure, but they don't always feel like they figured it out for themselves.

So, what do YOU do?

How large?

Easily 50 feet tall. It has goggley eyes with a hint of sickly yellow in the center. On the end of its tail is an enormous 8-ball, swinging around like a wrecking ball. It has a bright red collar. Instead of a tag, a giant pine air freshener, the size of a toolshed, swings from its neck.

What's it doing?

It trots down Route 666. Cars swerve out of its way. It growls at them, bends down and bites the road. It peels the pavement up off of the ground, like a strip of black licorice, and shakes it. Cars fly through the air and crash in dusty heaps of twisted metal. With chunks of asphalt dropping from between its teeth, it turns and looks at you. It seems to be smiling.

Smiling?

Sort of a mischievous grin. What do you do?

During the course of a game I ask the Players this question again and again: What do you do? It's their cue. They're on. It's their turn to be a hero, or die trying. That's what it's all about - what THEY do - the Players and their characters.

What they do needs to be left entirely up to them. It shouldn't be scripted. I've played in tons of games where the characters are being led through the story and nothing that they do seems to alter the story. I intentionally create situations for my Players that I don't have a solution to. I don't know how they're going to get out of the problem they've gotten into. This is usually when they come up with the most interesting solutions. If I spoon-feed them a solution, then they get through the adventure, but they don't always feel like they figured it out for themselves.

So, what do YOU do?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)